This important series of conversations was originally published on November 2, 2020 as part of Friedman Benda’s Design in Dialogue conversation series. In these conversations, Dr. Catharine Rossi – a UK-based design historian, and associate professor at Kingston University – speaks with Branzi about his long and influential career. Below is translated transcription of the first part of the conversation.

Part 2 – Andrea Branzi’s Design Approach: No Stop City and Beyond

Taking one of his most well-known projects, No Stop City (1969), as its departure, Branzi presents his ideas about urbanism and the history of utopias, framing these issues in relation to the contemporary politics of neoliberalism.

CR: Welcome back to Design in Dialogue, Andrea. I really valued our conversation yesterday.

AB: Me too.

CR: Good. We focused on the context in which you began your work. We also spent some time exploring the context… or the Radical and post-Radical strategies that you employed in the 1960s and all the way through to the 1980s. And I’m extremely pleased to be able to continue the conversation today. And today I would like to focus on a project, or rather a concept, that has defined your work. Obviously I’m referring to No-Stop City, developed by Archizoom Associati in 1969. What I’d like to discuss with you or ask you about today, is not only No-Stop City itself, but also its ramifications for your work, as well as its relevance and legacy today.

Okay, let’s get started. Let’s start out by trying to understand No-Stop City itself. In practical terms, what is No-Stop City? It seems like a simple question, but clearly it’s not. And what form does it take? What vision does it project? And how is it communicated? That would interest me.

AB: No-Stop City was the product of a very high-level debate. It was developed by our design studio, Archizoom, which was not only concerned with issues of design or economic matters, that is with the survival of the studio, which was very young. It was also an opportunity for a debate that was more cultural in nature, I would even say philosophical. It was an atmosphere highly charged with new and important impulses. This allowed us, as a group, to cultivate a mode of working that was entirely new. We didn’t just discuss politics, so to speak, or design, but also more profound concepts. No-Stop City is the product of an insight connected… to an… to an interpretation of the world of design as a highly-evolved system, that is in continuous transformation and is continuously growing. We didn’t think of architecture as just a profession, but as a space for understanding, for perceiving reality, for thinking.

And so No-Stop City is an insight that I have to say was immediately… understood by friends, by young architects, and even by theorists, as a kind of developmental vision of design, no longer tied to a perimeter, to a defined space, but rather as an idea in continuous development, in continuous transformation. This… in a certain sense… In my opinion, this is also connected to… other moments in the history of theoretical thinking, in the history of the world, starting, let’s say, with the Torah, with the sacred scripture of Jewish thought… The Torah is a kind of infinite ribbon, within which is contained all knowledge sacred, human, and so on.

But there were also other… many other important protagonists of the new culture of that time, such as… such as Jack Kerouac, for example, with “On the Road.” He wrote that… And it’s important to remember that Jack Kerouac was very close to Neal Cassady, who was also a Jew, as you can see by his name Cassady, i.e., Chassidic. This book, “On the Road,” is a grand infinite ribbon along which the narrative develops continuously. But there were also other authors, obviously, who in that period began to view creativity as a permanent transformation. Philip Glass, for example, in the realm of music. He provides us with an interpretation of sound as a continuous path that is no longer represented by the traditional composition of music. There is no overture followed by a central theme and then a finale. Here in contrast… in the case of Philip Glass, the music does not have a precise beginning or end. Rather it’s an eternal music that passes through space, a continuous environment.

CR: So in your view, No-Stop City was the first attempt to translate, let’s say, this new mode of thinking about creativity, this concept of eternal, continuous, developmental creations. No-Stop City was perhaps the first attempt along these lines in the world of architecture.

AB: Yes, although it’s not an antagonistic idea. It’s not in conflict with anything. Rather it’s a thought in continuous transformation. It doesn’t belong to the past and the future but to a continuous present. It’s something that is not precisely articulated. Rather it belongs to another kind of intellectual process that is still a part of me in a certain sense, regardless of how long ago it was, and how different it is from the subject of my recent work. However, that kind of work…This also means working without an endpoint to reach, without a conclusion, but rather engaging in an everlasting search. Indeed, it’s a kind of boundless contradiction, devoid of conflicts that in some sense end, for better or for worse. It’s a continuous present.

The idea of a continuous present that is of course also part of other levels of… Nietzsche, for example, has the idea of eternal return. Or… the tragic poets, the Stoics. But also, for example… Think of… Carnac, the prehistoric site with standing stones that are lined up in rows, in order of size from largest to smallest, but that nevertheless constitute something that has no precise beginning, that has no endpoint, and that has no precise meaning. It’s like a sacred gesture that can be continually repeated.

CR: It’s interesting to hear about all these… these influences, let’s say, and also these comparisons. I was particularly interested to hear you say that No-Stop City is not confrontational or antagonistic. And I see that. As a project, I see that. But I’m also interested… Because I’ve been reading the work of Pier Vittorio Aureli, who describes the project very well. And he describes the project as antagonistic, in the sense that it’s a critique of the capitalist city, of bourgeois ideology. And with that perspective it could be seen as antagonistic in a certain sense. Is that right or not?

AB: Sure. You could definitely say that we come from a left-wing culture, but that doesn’t change the fact that there’s a continuous sign. On the contrary, left-wing culture grows out of a continuous debate that stimulates development. So it’s fed not so much by a conflict but by a continuous intellectual tension. It’s a creative way of thinking that never ends. After all, in the history of art this is all pretty obvious. There aren’t just historical periods and styles of expression, but rather a continuous evolution in the development of a creative mode of thinking that never goes out of existence. Sometimes it frays, appearing to lose its purpose. But then it returns again in pressure, in energy. So there should never be a definitive judgment about art. Art is something that moves in the direction of other horizons. It’s a dynamic form of energy that runs through history, the history of human work and thought.

CR: But I’d like to know… Indeed, we talked about it a bit yesterday. I’d like to know how political it was. How much was No-Stop City animated by “activism,” as we say in English? Or maybe it wasn’t.

AB: Well, it’s an energy, not a conflict. A conflict ends in some way. It has to come to an end. Energy, on the other hand, is something that goes through different phases, all the while progressing in a direction that is never completely defined. It evolves over time. Sometimes it seems to break down in useless activity. On the other hand, it sometimes achieves a great concentration that is very recognizable. But if we think of the history of art, even the more recent history of art, or the modern history of art, we trace a path that always arrives at a point that seems definitive, but then suddenly it opens up again. Think of Jackson Pollock, for example. He began by experimenting a lot with action painting that still had recognizable signs, but then he finished with this infinite dance of signs… Here we also have a kind of continuous ribbon of signs, of marks, that don’t have a precise meaning.

In fact, at the beginning, this type of work was rejected out of hand because it seemed like the scratches of a child, like senseless scribbling. But then all of a sudden this empty tension takes on meaning. The scribbling of children is actually a kind of creativity that is very similar to that of Jack Kerouac… No, to that of Jackson Pollock. Because all children are artists. But then over time there’s a progressive selection, on account of which only about one in a thousand creative people are still artists. This person can then decide to make a profession out of an activity that initially is very chaotic, when engaged in by a child. But all children are artists.

CR: This is an idea that interested Dalisi, right? Riccardo Dalisi was very interested in the creativity of children. Also in that period.

AB: Yes, Riccardo Dalisi’s work is connected to the children in the markets of Naples but… However, there’s always a figurative element in Dalisi’s work.

CR: That’s true.

AB: They’re objects that have… They’re identifiable. Whereas sometimes what’s interesting is the moment when there’s no meaning anymore. It’s just pure physical, mental, intellectual energy. It’s not a narrative. Or it’s a continuous song. It’s not music that has a beginning and an end. No, go ahead.

CR: Thinking about how No-Stop City was received… Because when you mentioned Pollock, what comes to mind is not simply Pollock’s works, but also the photographs of him making those signs on the canvas. I’d like to know how No-Stop City entered the world, and how this is related to how the project has been received, experienced, and understood. Because it was published for the first time in “Casabella,” right? In 1970?

AB: Yes.

CR: And this may just be a technical issue, but I’d like to know why that magazine, or what it was about the pages of that magazine, that made you see it as the proper platform for disseminating this project.

AB: When it was published in “Casabella” let’s say… the project received a great deal of scrutiny, but it was not understood, and rightly so. It wasn’t…

CR: I believe that.

AB: It wasn’t rejected. On the contrary. Many people were intrigued by that kind of hypothesis. However… Ultimately they were not… understood perfectly. But that was also fitting, as it couldn’t have been otherwise. Indeed, it was the result of things that weren’t always clear even to us. It wasn’t simply clear and obvious. In fact, there was a lot of discussion about the hypothesis of the end of work, which is a topic about which… Let’s take the mass production of ideas, for example. It was a hot topic in political philosophy at the time, but it was also very difficult to interpret because it was still a more advanced aspect of Marxist thought, and it wasn’t exactly clear what it might mean or signify. Not even to us, and we were the ones developing the approach. But that’s normal for art. Those who do a certain kind of art aren’t necessarily the best people to explain it. Those are different things.

CR: In fact, you already explained or communicated it in the images. It’s not like it’s also necessary to have the words to explain it again.

AB: Right, it’s not like… Jackson Pollock never explained, and no one ever asked him to, except for a few misunderstandings that cropped up. But it’s not the job of a creative talent to precisely explain their own work. That’s a different… It comes later, much later, gradually, amidst a thousand difficulties. Nevertheless, there is a kind of pressure to do something. For example, with Pollock… And this may be one of the more meaningful examples. With Pollock, the effort of explaining his art is clearly useless. You can’t explain, you can’t… Any effort to explain it ends in disaster. It’s a mistake.

It’s like with art in general. Artists… I’ve known many artists, painters, for example, who… When you talk about them, or when you talk with painters and they reflect on the paintings they’re working on, they always talk about them… At least I’ve heard this many times. They talk as if they’re talking about gastronomy. As if they’re talking about making things to eat. About food. They describe their work as heavier, as lighter, as more fragrant, that it interprets colors in a very physical way.

There’s a whole way of describing art as if it were artisanal. But not in an aesthetic sense. In a physical sense. With a kind of gluttony. Saying that something is delicious or very sour, poisonous, dark. But it’s never explained philosophically, so to speak. Rather it’s described physically, artisanally.

CR: Thinking about the problem of the impossibility of finding the proper words. At least during the period in which the project came into being. I’m interested in the role, if that’s the right word, of the installation, or environment, that Archizoom created for “The New Domestic Landscape.” Because that seems to me to be a continuation of the idea behind No-Stop City. Did that project represent for you another attempt at elaborating on No-Stop City, or was it something different for you?

AB: No, well… Also in this case… This mode of representing architecture as something that never develops in a definitive way, but that transforms, expands… is also the result of a critical vision of modern architecture. So… So, it understood the limit of the concept of modernity. Because the concept of modernity is still entirely tied to the idea of a past and a future, whereas… that vision is replaced here by the idea of a continuous present. It’s something that moves and so cannot be grasped, cannot be defined. This seems to be something very important, and something very different from the historical notion of modern architecture and the architecture of the past, which has its own charms. But there’s also an aspect of nonsense, something that can’t be precisely explained, as is the case in the world of art, in music, in poetry. There’s always… In literature there’s the limit of the story, of the novel, of the novella, which in contrast has a beginning and an end, as well as an arc clearly delineated by episodes. But in other types of art there’s constant sound, a constant vibration.

CR: Even if the project was never fully understood at all times, it’s striking that there was constant interest in the project, from the 1960s down to today. We’re talking about it right now. Why do you think it has had such constant appeal? Because it has relevance? Yes, perhaps the project has always been relevant.

AB: Yes, there’s an evolution, but it doesn’t have time limits. The things people are doing nowadays in architecture, which are so different from things of the past, are nevertheless still part of it. They’re still accompanied by a gradual loss of meaning. Ultimately, what’s architecture good for? Then… it turns out that it’s only an opportunity to express a hypothesis. In any case, they’re all individual episodes, each different from the another. There are no two… two dwellings, two houses in the world, that are exactly the same. Every occasion is different from the others. And continuous. And objects are even more complicated. They’re always fleeting, full of meaning. Objects are much richer than the architecture itself. They don’t have a precise definition.

CR: Do you think that if Archizoom or you redid No-Stop City today, are there elements that you would have conceived, or would like to conceive or communicate differently than you did in the No-Stop City of 1969? Or not.

AB: I don’t know. Maybe not. There was an American theorist who was a great influence on us. His name was Kevin Lynch. Kevin Lynch was the first to speak about a kind of continuous ribbon. It wasn’t so much composed of built things as it was of a continuous variation of… meetings of roads, of paths, where you can find not monuments, but rather everyday objects. For example, the bar, the newsstand, the… the subway platform. It’s composed of a series of minimal episodes that constitute the true urban experience, the true urban life, which is not composed of architecture, but rather of… the presence of these micro-environments that are met with along the paths of the city. Human paths.

CR: Everyday paths.

AB: In this sense, Kevin Lynch was one of the theorists, one of the American urban planners, who finally developed a vision devoid of stages and devoid of symbols of modernity. Some routine thing that happens without any precise design. The urban network is something that is never interrupted, that transforms. It doesn’t have a clear, connective, total sense. This vision was very important for us. I believe he wrote at the beginning of the 1960s. A very intelligent urban planner and theorist. He was very new, very new and very fresh.

CR: So to understand how your thinking has developed from that project to today… Because in a bit we’ll talk about a few projects in particular at the level of design. So it seems to me… Or it might be… It seems right to say that it’s not a true capitalist critique that runs through your work. Nor is technology the thread that runs through everything, although it’s a topic that fascinates you. Rather it’s the urban condition, let’s say, or the urban condition in modernity and in post-modernity, if we can use that word.

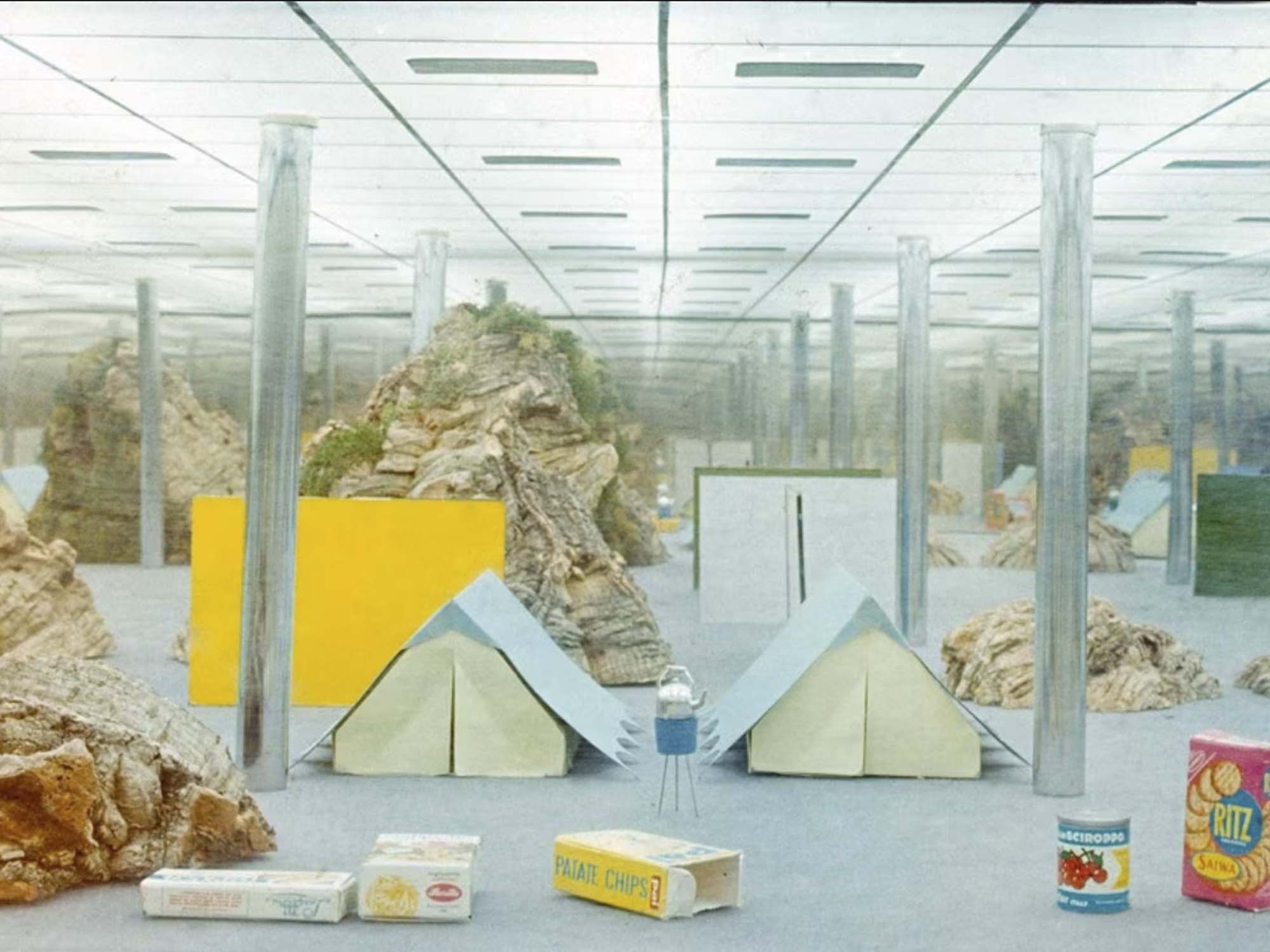

AB: That may be the case, although it’s never been clear. And maybe the connections of this… Maybe it can’t be all that obvious. But this kind of… comparison with the infinite dimension of the environment… For example, it’s already present in those images, those models that were constructed, let’s say, at the beginning of the 1970s with mirrors. I always used… I very often used the mirror, or mirrors, to represent the infinite multiplication of images. Thus to show that they have no beginning and no end. They’re like self-multiplications of a sign that, when placed between two mirrors, becomes a kind of infinity that’s clear, that transcends the dimensions of an architectural model. That’s more mental than physical.

CR: Yes, it’s almost universal. There’s a sense of the universe when you look in a series of mirrors.

AB: But in the Renaissance, for example, the idea of infinity is present. Because the law of perspective comes from the idea of being abl to represent infinity, i.e., the horizon. It’s something that’s present in Western culture, whereas in medieval culture everything stops, gets stuck at a certain point. It becomes definitive, rigid, whereas in the Renaissance there’s this idea of arrangement, of perspective, that, like the theoretical philosophers said, is of a symbolic nature, a philosophical nature. It’s not exactly a law of perspective. It’s a way of representing thought that is organized on an infinite ribbon, that goes towards infinity.

CR: That’s interesting because… Sorry.

AB: So, this kind of development, which is unlimited, infinite, continuously repeatable, is present, is present in history, in the history of architecture from the Renaissance onwards.

CR: Yesterday we saw that this idea of infinity and… The tension between the infinite and the finite is something that you have explored in the design of furniture, which you called “Infinite Furniture.” So I’d like to move on now to thinking about furniture. Because even though No-Stop City is about architecture or urban planning, the concept of No-Stop City also includes furniture and indeed all the elements of life in a certain sense. There’s a project that interests me a great deal, that at first sight, in its materiality, in its appearance, in everything, seems to be totally different from No-Stop City, but actually, as far as I understand, it’s part of that idea. And that’s “Animali Domestici,” the furniture from 1985 that you did together with Nicoletta Morozzi. So I would like to understand how this furniture can be seen as part of the idea behind No-Stop City. Or where does this furniture come from?

AB: There’s a shift in the idea. It goes from the last… from the Memphis Group and the experience of New Italian Design to a neoprimitive dimension. It’s not an ecological stance. That has nothing to do with it. Rather, the idea is… Because the primitive concept is one in which there is no… Like in the thought of primitive human beings, in which there is no past, there is no understanding of history. Nor of the future, of civilization, of… And primitive human beings are very similar to us. They have a continuous present and not a past and a future. Rather they always live in a continuous present that evolves without interruption. In this sense, the creativity we see in New Italian Design is not so different from that found in the evolution of the neoprimitives. In a certain sense, it’s the same existential condition that doesn’t change. Or it only appears to change. Then it takes up this type of continuous sound again that changes, but that is never interrupted.

CR: That’s something that interested the anthropologist Lévi-Strauss. And you also see it in the exploration undertaken by Superstudio in the 1960s and 1970s, I believe. Design shows an interest in the attitude of the anthropologist when it searches for new vocabularies to explore.

AB: The difference between the work done by our group, Archizoom, and that done by Superstudio is an important one though, because for us it’s always the search for a city without architecture, where there are only micro-organisms, micro-objects. Whereas in Superstudio, there’s an architecture without the city, composed of monuments that are very rigid, very well-defined, and well-represented. It’s the opposite. They’re two visions that the Radical movement expressed. They’re two strategies that are utterly opposed to one another.

CR: Of course, it’s impossible to imagine “Animali Domestici”… Only you and Nicoletta could be the creators of that project. But “Animali Domestici” also evokes a word that we haven’t mentioned so far, and that’s “hybridity.” That’s the “neo” in neoprimitivism, I imagine, in the sense that there’s this very visible combination of different cultures of design. There’s the wood of the tree and then there’s MDF, a material that is much more industrial. So this hybridity, or dichotomy… I’m not sure which is the right word. Does it represent a shift, a new chapter, or do you think it’s something that develops out of No-Stop City?

AB: Yes, it’s a continuation. There’s no interruption. There’s no interruption because it doesn’t distinguish the past from the future, because it doesn’t correspond to distinct historical episodes, but rather to a continuous narrative, to a mirror-like… vision of the world, like the mirrors that multiply and change, but are ultimately always continuous, infinite environments. So they’re considerations that are difficult to define. Because they happen, and either they’re understood or they’re not. There’s no… What I’ve been doing for the last couple days, for example, is a series of designs that appear to be individual projects, but that are actually repeated almost ad infinitum with many variations, but without any ultimate meaning. So the idea is the same, only now I’m trying to surprise myself.

CR: That’s a wonderful thing to do. This all makes me think of “Genetic Tales,” the project you did in 2000 for Alessi. It was a graphic program, let’s say, with many, many, many, almost an infinite number of sketches of faces and people. Is it right to think of this project as well in combination with this sense of infinity?

AB: Yes, it may be that Alessi… “Genetic Tales.” Ah, you’re talking about “Genetic Tales.”

CR: Yes, that’s right.

AB: Okay. Of course. Also this… progression towards infinity, for example these faces… “Genetic Tales” is contained in a book where there’s a whole series of cases, some unpredictable, some predictable, of familial relationships, of encounters with animals, and so on. But there’s another image that I produced, that also seems to have no rationale. It was a series of tiny faces, of tiny expressions that I repeated in the thousands, each one slightly different from the other. For example, this work shows genetic transformations in progress, such that no two faces resemble each other. The faces are never… related by blood. They’re always fleeting.

It’s a bit like as if they were animated by an energy that never ends, but somewhat resembles, you could say, the energy of the moon, which every night for millions of centuries, has lifted up all the oceans of the world. Only at night, it lifts up the oceans without ever making a sound. A perfect silence. Everything is lifted up. At night it rises, and then with the sun it goes back down. And then… So it produces this enormous energy that has no beginning or end, but that is connected to the cycles of the existence of the cosmos. And it’s never complete. And these massive liftings of the oceans don’t make any noise. They never end, because the next night the oceans are lifted up again. And then with a breath, like a human breath…

CR: This is almost like poetry. I like this description very much. Although there’s never silence in London, so there’s always noise when the moon lifts up the oceans. But I think about it. Perhaps to conclude our conversation about “Animali Domestici,” I think “hybridity” might not be the right word, because from the neoprimitive perspective there’s no difference, there are no different elements to combine in a hybrid. So even the very word “hybridity” is a problem. Does that make sense? The point is that I can’t find the right word to understand and to articulate “Animali Domestici.”

AB: I myself never find the right words to describe No-Stop City, for example. In fact, each time we have to make a series of comparisons, saying it’s like this or that, and interpret it provisionally. But maybe it has to be like an intuition, a mental… intuition, a dream that at times can also be a nightmare. It’s not always the same, but it’s a fruitless idea. It doesn’t legitimize anything. It doesn’t explain anything. Because it’s just something that happens and doesn’t have a clear purpose. And maybe it’s fine that it doesn’t have one. But art has existed ever since there have been human beings. Ever since children have existed, they have been creative. What does that mean? What does it mean that children are creative? I don’t know. Maybe some pedagogue has explained it. But explaining it doesn’t get you… It doesn’t get you anything. Because children change, stop, or… they transform into adults who no longer have any connection to creativity. So it all breaks down into a genetic energy that never ends. I think the right thing is to not try too hard to explain it. Because either you get it or you don’t…

CR: That’s true.

AB: … or you don’t get it. Where does poetry come from? Poets who go through life… Poets go through… They’ve always intrigued me, because they go through life with all its difficulties, its complexities, its contradictions, without… without anyone having asked them to do it. No one ever asked them to write poetry. No one paid for it. No one buys it. Nevertheless, they continue to do this useless thing which is also wonderful and indispensable but totally unjustifiable. Because very often they’re disasters that are ugly… And suddenly what was ugly becomes a masterpiece. Or a masterpiece becomes a trifle, totally banal. It’s a nocturnal energy, a lunar energy, that lifts something up and then puts it back down, and then lifts it up again. But if you try to explain it, you can’t.

CR: It’s interesting that you’ve used the word “energy” a lot today. It seems to me like a good word for at least trying to articulate this. And when you were talking about children, saying that…

AB: About what?

CR: Children and creativity. It makes me think of how games and play are very important for children. For us adults too. It’s anthropological, existential.

AB: Indeed, it may be one of the most enduring activities for human beings, including adults.

CR: And therefore, and I could be totally wrong here, but another project, another object I’d like to ask you about is a light from 1988: the “Foglia” light, or “Leaf” light, which was one of the last objects you designed for the Memphis Group. I’ve had to think about that object a lot, and I wonder if “game” is a proper word for understanding it, because… I remember reading Anthony Dunne, the English designer. He’s a proponent of Critical Design. And he described how influential… that light was, as it was a technological object that was important and progressive, from both the conceptual and the technological point of view. So I’d like to understand if you consider those two things, technological and conceptual innovation, as separate, as a dichotomy. Is that right, and is the word “game”… Perhaps the light is a kind of game. Is that a word that can help us to understand this object?

AB: Well… the “Foglia” light is somewhat the result of a… an interpretation of animism. Of something that… can at times be menacing. I saw some Indian territories inhabited by animists. They put red paint on a rock or a spring. They see the holy in nature in an unexpected way. They see it in nature like a mysterious energy. So this light… is the product of this… is a representation of animism, of something that’s hidden in the trees or in the stones, and that doesn’t modify the objects, but bears witness to something mysterious, holy, unknown. I don’t know the person you mentioned, this English designer, who wrote about the “Foglia” light. I’d be grateful if you sent me the details.

CR: Yes, I’ll do it later. His work is very interesting.

AB: What’s his name?

CR: Anthony Dunne. He works with a woman named Fiona Raby. They’re Dunne and Raby. I’ll send it to you.

AB: Thank you.

CR: No problem. So, once again we’re almost at the end of our time together, and it seems like we’ve barely begun to talk about No-Stop City. So maybe we should proceed to the objects that seem to me, to have been influenced by the idea behind the No-Stop City project. One of the threads, let’s say, is the idea of the relationship between architecture and the city, but also the possibilities of architecture and the city. I read, although I don’t know where, that you described your interest in the failure of both architecture and design, to confront the challenges of the 20th and maybe the 21st century. And so the objects you have produced or have designed, such as the many dioramas and models, and perhaps also “Planks” from 2016, have this quality of autonomy. And for you, this autonomy is an expression of this failure. And I’d like to understand better if you still think architecture and design are somehow incapable, and what strategies there are for avoiding or confronting this failure?

AB: Perhaps the term “failure,” which I have used at times, is a bit too rigid, too severe. I’d call them mutations maybe, or transformations, rather than failures. In part because… In these stories failure doesn’t exist, because there’s also no victory. Defeat is always understood as a moment that is a part of transformation, of mutation, of modifications. However, if we consider… design culture, architecture is certainly the product, is always the product of a failure, of something that was supposed to be done but wasn’t done, and so produces an exception, something different. Therefore… it’s always necessary to do something different from what’s been done up to that point. And this is essentially the history of architecture. An infinite series of variations, of episodes that are all different from one another, and what we talked about before, namely that there are no two houses that are exactly the same in the whole world.

Every moment is different, and so on. And this applies even more to objects. Objects are multiplied but are continually transformed. How many chairs have we produced in the world? They’re all different. And without there being any urgent need for chairs that are all different. Right? But… But an extremely earnest commitment to producing glasses that are all unique… It’s like how artists keep painting one picture, each different from the another, without interruption, without a reason. It’s like an energy of continuous and useless transformation adhering to some rational control. We have to admit that these are useless activities that cost a ton of energy and money, effort and experimentation, without reaching a conclusion. There are historical periods, different styles, different techniques, different frameworks, all for doing something that’s of no use to anyone. But it’s the most extraordinary thing in human history. This purely poetic, purely artistic, purely creative activity, that no one… no one pays for, no one asked for, no one buys, but it’s absolutely, extraordinarily fascinating.

Right, it’s not about what the world or humanity needs. It’s about what the creator needs And us too, right? There’s a tension here. With this in mind… I’d like to end today with a question that’s a bit lighter, since we’ve explored rather theoretical things today. But maybe it’s not light for you. It regards another installation, more recent than… well, from 2008, at the Fondation Cartier in Paris. I’m talking about “Open Enclosures,” which seems to explore the themes of hybridity, flexibility, nature, the city, and their interplay. There seems to me to be a thread running between it and No-Stop City. But that’s not what I want to ask about. When I was watching the video about the project on the Internet… Unfortunately, I didn’t see it live… I loved Patti Smith’s unexpected presence in the installation. Yesterday we also talked about music, about the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. And considering that in the third episode tomorrow we’ll talk about the cultural side of design, I’d like to know what it is about Smith, or about music in general, that attracted you for this installation? And also what is the role of music in general in your work? In fact, you mentioned Philip Glass as well today.

The encounter with Patti Smith happened pretty much by accident. It was organized there in Paris. There were two spaces, two locations, one for Patti Smith, and one for my work. And we developed a fondness for each other. And she even wrote some music for my work there.

CR: Fantastic.

AB: These are… These are experiences and encounters that happen in the world of culture and art. They’re not strictly related to one another. These encounters are always a bit miraculous but nevertheless very stimulating. They’re always stimulating, always interesting. The connection to music… For example, the twelve-tone music of… Schönberg… of Schönberg. In a certain sense, twelve-tone music is… has a character akin to a kind of continuous homogenization of music, which is no longer distinguished by sharps and the rules of musical composition, but rather is a continuous linear sound. It then continues in contemporary music. But it’s a mode of smoothing out all of the compositional exceptions into a single auditory narrative, that in a certain sense resembles a kind of No-Stop City of sound, of music, which is not the law of acoustics but rather is the law of dissonance, because it introduces into music the contradictions of music, the smoothing out of music. In fact, he used to say that to save music, you had to destroy it.

What he meant was escaping from the idea of the concert, of the traditional auditory event, and progressing towards other dimensions, to other… where the music is also antagonistic, and also noise, and also unpredictability. In fact, the path taken was to connect… to finally escape from the myth in which the great… contemporary musicians like Luciano Berio, like Luigi Nono, got on the nerves of entire generations of performers because they wanted to affirm that the new music had to be performed at La Scala. That is, in the historic theaters. And he made every effort, so to speak, to find acceptance for a kind of music that was as antagonistic and sour as contemporary music, in order to have it accepted in the sacred abodes of the theater. But in the end, the true new music is that which was produced in the studios of… of American artists. It’s a music that is utterly experimental, unpredictable, where there are things to see and not only to hear. It’s a totally different dimension that has to finally be accepted and not still be obsessed with being invited to La Scala, the sacred theater of the music of Verdi. And that’s fine. Verdi has his music. We have our own music, and we do it somewhere else, somewhere that is not the official theater.

CR: Your description of music and the kinds of music that mean something to you, seems to offer many words and concepts that have an affinity with No-Stop City. In fact, you said, “I have written that to save architecture, you have to destroy it.” That seems to be a fundamental idea of No-Stop City. Unfortunately, at this point we have to interrupt our conversation yet again, because we’ve come to the end of another hour together. But I’m very grateful that we have one more day to talk together and to speak at greater length about the concept of design culture, and also about a cultural understanding of your work. Again, all that remains is to thank you and Nicoletta for today.

AB: Our conversation is very stimulating for me.

CR: For me too, obviously.

AB: I’m learning a lot.

CR: You’re learning? No! I’m the one who has something to learn here.

AB: No, this encourages me to reflect and to say things that on other occasions I might not have known how to say. In fact, I hope that my responses have been useful for you, but these discussions have also been very useful for me.

CR: You have no idea how happy I am to hear that. I’m truly very thankful. Well, tomorrow will be even more interesting.

AB: Good. I look forward to it.

CR: See you tomorrow. Bye, Andrea.

AB: Bye, good luck. Thanks.

CR: Thank you. Bye.