By Mario Ballesteros

Nestled in the rugged, semi-arid Mixteca region in Puebla, Mexico, Santo Domingo Tonahuixtla is a tiny and remote village of 700 inhabitants. In Náhuatl, Tonahuixtla means “place of burning thorns,” an evocative name for this secluded but hardy community, where the bond between life and land has been cultivated across generations. For centuries, the town has been growing corn as its main source of sustenance. In the past few decades, though, Tonahuixtla, like many other rural places in Mexico, has been battered by poverty, erosion and desertification, generational struggles, forced migration, and the looming threat of climate crisis.

This is the unlikely context for the work of Fernando Laposse. Unlikely because he has spent most of his life skipping back and forth between Mexico City and Europe, and the better part of his formative years in the buzzy classrooms of Central Saint Martins, and then working in some of the most exacting design studios of London, a city he called home for over a decade and where he began experimenting with natural materials and fibers. However, an intimate family connection to Tonahuixtla had been established during his childhood, when his parents sent Fernando and his sister to spend summers in the village under the watchful care of Delfino Martínez Gil, a prominent town figure who also happened to be employed by Laposse’s father.

The seed of this experience was sown so deep in Fernando that, even though it had been buried in his past, it sprouted decades later, with an intensity that was hard to ignore. By rekindling his connection to Tonahuixtla, Fernando Laposse shaped his voice and his calling as a designer: a path leading toward the regeneration of a community. Through intricate, deep-seated connections—both social and emotional—established in those early years, Laposse unearthed a sense of purpose that would bridge his past to a future vision: a plan for systemic transformation. Corn would be at the heart of the undertaking.

It all began with totomoxtle, the unassuming dried husks that Fernando chose to work with in the First Food Residency program fostered by the British Council in Oaxaca, at the Centro de las Artes de San Agustín, which he attended in 2014. The program focused on creative approaches to climate change and food sustainability. In Oaxaca, Laposse found a hotbed of political activism and cultural debate centered on the defense of native corn varieties against the encroachment of transgenic crops. He sought to contribute to this vital conversation by enhancing the commercial potential of heirloom varieties, employing the transformative power of design.

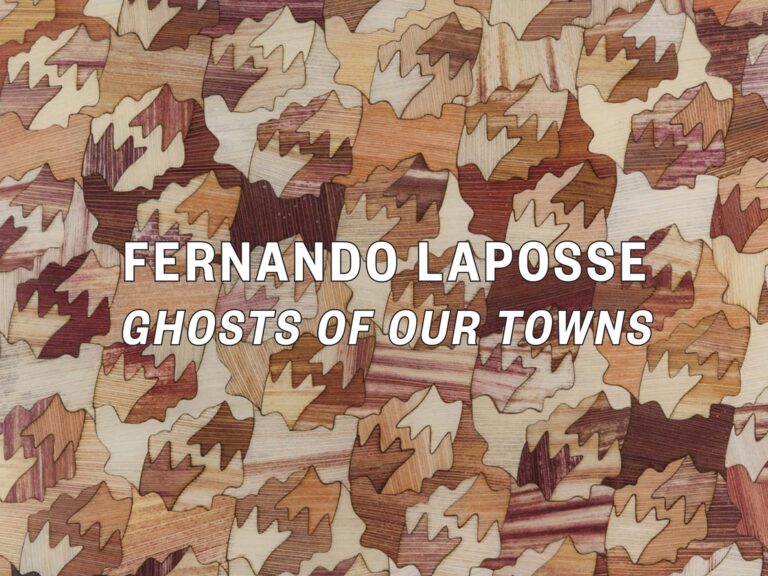

The idea was simple: to breathe new life into totomoxtle, a byproduct often relegated to waste or livestock feed, and transform it into a sustainable and emotionally evocative material for crafting unique design objects. The remarkable spectrum of natural colors found in the leaves, ranging from vibrant purples and deep reds to creamy whites, carried a unique aesthetic opportunity. Fernando incorporated this diverse palette into a marquetry-style surface that would be suitable for application to walls and large-scale furniture, yet intricate enough for smaller objects like lamps and flower vases. In the process of elevating the humble husk, Fernando also created an additional source of income and therefore a compelling incentive to return to cultivating native Mexican varieties, even though they were less efficient in terms of yield compared to hybrids and GMO varieties. After producing a few formal experiments with the corn leaf veneer, he wanted to scale the project, and immediately thought of Tonahuixtla as the perfect testing ground.

When Laposse returned to the town after a ten-year-long absence, he found a dramatically different place from the one he remembered and cherished. The place felt desolate. Ancestral milpas —small plots where corn, beans, squash, and other crops once thrived—lay abandoned and forlorn. The adverse impacts of intensive agro-industrial practices, coupled with climate change, had taken a toll on the land and driven many of the town’s people to look for opportunities elsewhere. The dire circumstances in Tonahuixtla marked a profound shift for Laposse and his Totomoxtle project, prompting a shift from an individual creative exploration to a comprehensive, long-term community initiative. For him, it was more than a design project; it was a matter of creating a lifeline for a town in need of opportunities.

Laposse’s ambition extended far beyond the present. He envisioned a future where Totomoxtle could transform Tonahuixtla for the better. The collaborative nature of the project was vital from the beginning, in order to adapt to the communal organization and property structure of the ejido which is the base of collective decision-making processes in the village. He devised a twofold strategy: to reintroduce native corn varieties, and create new skills and jobs within the community. He brought key allies on board, including the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), an agricultural research non-profit dedicated to improving seeds as well as the livelihoods of small-scale farmers in developing countries through sustainable practices.

By replacing hybrid seeds — which can only be grown once and need to be purchased annually — with native varieties capable of being stored and replanted without relying on chemical pesticides and fertilizers, the Totomoxtle project has granted local farmers in Tonahuixtla greater autonomy and control over their crops, as well as the chance to become more self-sufficient in food production. In the almost ten years since Fernando began collaborating with local farmers, the project has also played a significant role in elevating soil quality, gradually curbing erosion and alleviating the negative impacts of intensive agriculture. Finally, it has bolstered the town’s income by repurposing corn husks within the Totomoxtle project, all within a circular framework. The profits from the project pay for an advance given to every farmer in town that plants native seeds to prepare the land and use the milpa system. The seeds are given away for free by the community seed bank. During the harvest, the farmers that choose to use Laposse’s custom-designed dehusking machines get paid extra. After the harvest, the leaves are transformed into variations of the Totomoxtle veneer.

Many of the town’s families are involved directly or indirectly with the project, either participating as farmers or contributing to the production of craft and design objects utilizing the Totomoxtle marquetry. Recently, the initiative has expanded to establish a self-sustaining workshop and community center that is used for both town assemblies and manufacturing totomoxtle. Here, local women and men might be planning a local festivity; discussing politics or deciding what to grow on communal lands for the next harvest one day; or drying, cutting, ironing and assembling corn husks into vibrant, polychromatic patterns. Before Totomoxtle, there was no real preexisting craft tradition alive in Tonahuixtla to tap into. The choice of establishing a workshop in a community without any specialized artisans who could easily be employed as skilled labor — as is typically common with many designers in Mexico — was deliberate. Laposse’s goal was to empower and cultivate new skills, not simply to modify existing artisanal practices. Instead of acting as a simple intermediary, he built a symbiotic partnership, investing in the community and cultivating a new sense of pride.

The shared knowledge that is the base of the traditional communal organization of Tonahuixtla has profoundly influenced the project, in numerous ways. One of the most successful varieties of corn that has been reintroduced came not from the CIMMYT seed bank, but from a 90-year-old villager that had kept the seeds safely at home for years. Another recent milestone, which embodies the project’s deep collaborative nature, is the development of a new subspecies of corn with a husk that is a subtle shade of pink. This was achieved by cross-pollinating a native white corn with a red one and selecting the best qualities of both, which is what they have done for generations. This new range of colors of totomoxtle was incorporated into Laposse’s Kumiko cabinet series, in a beautiful example of how the townspeople’s tacit agricultural knowledge has become a key co-designing element.

The most powerful legacy of Laposse’s Totomoxtle experiment transcends design, seeping into the social and environmental fabric of Tonahuixtla. This journey traverses not just physical landscapes, but also cultural ones. The appropriation of the project through community involvement and guardianship highlights a shift in mentalities on both sides of the equation. A transformation of values, a restoration of self-determination, power and purpose for a community of proactive contributors. It’s a transition that resonates with Laposse’s aspirations—to place the project’s control firmly in the hands of the community, ensuring its continuity and growth.

Laposse has delivered a powerful proof of concept to the existential question of what design can actually do. When it goes beyond aesthetics or superficial and capricious markets, it actually can be a catalyst for change—a reminder that design has the power to shape identity, to redefine age-old narratives, and to restore dignity to communities marginalized by circumstance. Laposse proposes a model that trascends conventional norms of trend-driven design and advocates for long-lasting change. Totomoxtle stands as testament to design as a force that elevates not only materials, but also elevates lives.