Photography by Erik & Petra Hesmerg

By Simon Andrews

Ettore Sottsass Jr. (1917-2007) endures as one of the most significant, versatile and influential architect-designers of the twentieth century, whose intuitive capacity for innovation and expression was able to define the emotive capacities of communication through form. Fluently skilled across all media, from architecture to craft, from photography to jewelry, the diversity of his oeuvre consistently delivers meaningful structures that are guided by thoughtful metaphor. His work has been the subject of major retrospectives at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2006), the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2017), the Triennale Museum, Milan (2017-18), and most recently the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (2021-22).

Born in Habsburgian Innsbruck to an architect father originally trained under the Viennese Successionist Otto Wagner, Sottsass’ was to be a life of discovery and investigation that paralleled the migrations of a modern society now internationalized. His early years as an adolescent and student in Turin were followed by wartime postings to the isolated mountains of Yugoslavia, initiating a respect for the thoughtfulness of the region’s vernacular craft. His 1949 marriage to the literary intellectual Fernanda Pivano brought introduction to the great modern American writers — first Hemingway, and later Kerouac, Ginsberg and Burroughs — establishing a transatlantic cultural bridgehead that would soon lead to a residency working in George Nelson’s design office in New York in 1956. He sought out the pioneering gallerist Betty Parsons, whose gallery on 57th Street presented works by the new avant-garde, to include Pollock, Kelly and Rothko, and she agreed to try to sell his abstract drawings. Those brief months absorbing the effervescence of this modern city served as a touchstone for Sottsass — liberating creative certainty upon his return to Italy.

Exhibited at Milan’s Il Sestante gallery, Sottsass’ 1959 series of glazed ceramic Tondo celebrated wildly gestural marks and splashes of color that aligned with the intuitive energy of the Abstract Expressionists he had encountered two summers before. However, Sottsass’ interest was not merely stylistic — it was the experimental capture of wordless emotion or abstract energy, now in the reverential form of a sacred dish. For another series of Tondo designs around the same period, Sottsass emphasized ambient colorfields that evoked both the stripes and geometries of Ellsworth Kelly, or the resonant, meditative introspection of Rothko’s canvases. The designer had discovered within himself a capacity for visual communication that immediately set him apart from the consumerist interests that served mainstream retail. Emboldened, Sottsass evolved to interpret and adapt both shape and pattern now united as essential components not only of projects and commissions, but also for textiles, ceramics, metalwork and furniture design. Manufactured by Poltronova from 1958 until around 1964-65, this first generation of new furnishings employed grids, circles, cubes and rectangles both to enclose pattern or color, and to structure the essential form. There was clear echo to the early modernism of Josef Hoffmann, and to the Viennese gesamtkunstwerk of Sottsass’ Austrian heritage. Belied by their superficial simplicity, these clever furnishings aspired to deliver ambient, unobtrusive qualities to an interior.

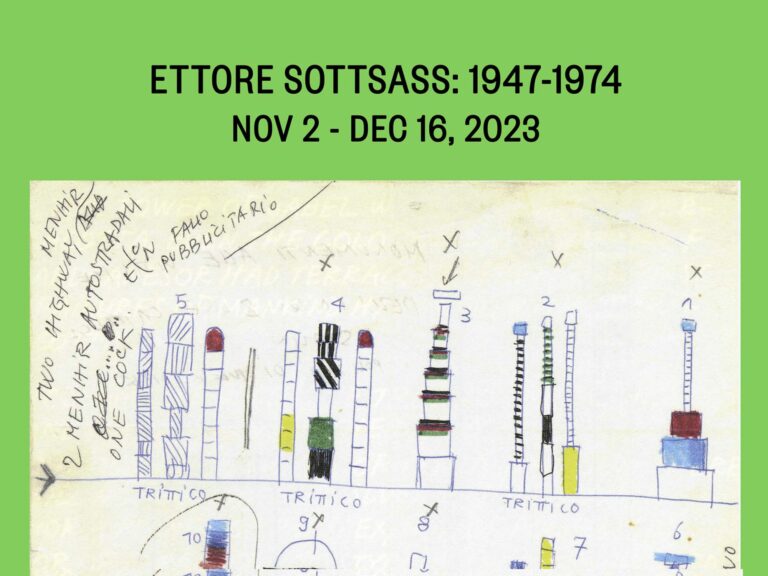

As the 1950s folded into an optimistic new decade, two seemingly unconnected events crystallized, inaugurating within the designer a certainty of vision that had until then only been tentatively felt. In 1958 Roberto Olivetti approached Sottsass with, at the time, what seemed like the opportunity of a lifetime — to assist with the design of one of the company’s first mainframe computers, the ELEA 9003. Enhanced by punctuations of color and of monumental, totemic form the computer’s casing became a major sculptural presence in the office environment, and was to serve as a conceptual template for Sottsass’ later ‘radical’ furniture. The ELEA would eventually metamorphose into myriad permutations of monolithic yet spiritually-resonant objects that soon included the Superbox, Totems and Grigi of the late 1960s, the consolidated living environments created for MoMA in 1973, and eventually the seminal Memphis designs of the 1980s. Through contacts made at Olivetti, Sottsass was also to undertake domestic commissions, including the two definitive interiors created for Nicola Tufarelli in 1959 and 1965, and the Milan apartment of Mario Tchou, 1961. These important interiors — both created for friends — provided Sottsass with the opportunity to deliver sincere environments that were fully holistic, fusing detail with service while invested with metaphor.

The second incident around this period was to prove more traumatic, yet no less influential. In 1961 Sottsass and Pivano toured India, Ceylon, Nepal, Burma and Thailand. The sensory, reverential culture of these environments proved inspirational, as did the absence of the consumerist materialism that was by now systematic throughout Europe and the US. Returning to Italy, Sottsass fell critically ill and with the support of Roberto Olivetti secured experimental treatment at Palo Alto, California in May 1962. The weeks spent in hospital, his senses dulled by cortisone and unable to sleep were to have a defining impact upon him — prompting introspection upon his role as a designer whilst at the same time immersing himself in eastern philosophies and stories of ancient cultures. This difficult period was to stimulate what would, upon his return to Milan in December 1962, evolve into a defining sense of certainty regarding the objectives and responsibilities of a designer’s duties to society. His recovery in California was also important for his exposure, throughout the summer and early autumn of 1962, to the emerging counter-culture by now evolving in San Francisco — a period during which he met both Ferlinghetti and Ginsberg, took photographs, produced collages, and printed his own improvised magazine, East 128 Chronicle. For those desperate, difficult months in California he was in exactly the right environment, and of responsive frame of mind, to now absorb with steely determination the anti-materialism of the emerging counter-culture, and to reflect upon its translation towards a European audience.

Within months of his return to Milan, the impact upon Sottsass of both his recovery and of the American counter-culture and Pop Art were immediately visible. His first major exhibition, in May 1963, was Ceramiche delle Tenebre (Ceramics of Darkness) — a hypnotically moody collection of standardized cylindrical vessels that drew unmistakeable reference to Warhol’s Soup Cans, first exhibited the previous July at the Ferus Gallery, Los Angeles. A Pop intent integrated into his designs for furniture — the Poltronova collections of 1965-66, within which the functionalist, color-coded performance of an Olivetti computer cross-pollinated with Pop to monumental, resonant effect. The branding that Sottsass agreed with Poltronova was both specific and resonant, accolading the works as if totemic entities — Barbarella, Lunak, or Tempus per Ingresso (Time by Entry)— and enhanced by careful photography that situated the works against the disruptive iconography of Warhol or Lichtenstein, or meditative Indian prints and soothing Chinese lanterns. The intention was clear, and the message unmistakeable, and the time for change was now. This was not furniture — these were altars for the rituals of domestic life.

Perhaps more so than through any other creative participant during this crucial era of the mid-1960s, it was Sottsass who implacably guided an intelligent, sensitive and humane exchange of progressive international ideas for design and living towards European embrace. His home on via Manzoni provided a vibrant platform to a rotating cast of passing talents, an intellectual and artistic crucible that at any given time may include Chet Baker or Umberto Eco, Gio Ponti or the millionaire activist Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, or Allen Ginsberg, with whom Sottsass and Pivano spent the summer of 1967. But by the following summer the skies had begun to darken, as discord disrupted both cities and campuses. Perhaps change was not so easy after all. One summer later still, 1969, and Italy would plunge into the trauma of two decades of anni di piombo. Reacting to the cultural zeitgeist at which he was himself at the centre, Sottsass would close out the decade with characteristically poignant and acerbic verve — the Yantra di Terracotta and the Mobili Grigi collections would offer opposing resonances towards a parallel interpretation of meaning, and assert new debate for a new decade.

— Simon Andrews, independent curator and advisor