This important series of conversations was originally published on November 2, 2020 as part of Friedman Benda’s Design in Dialogue conversation series. In these conversations, Dr. Catharine Rossi – a UK-based design historian, and associate professor at Kingston University – speaks with Branzi about his long and influential career. Below is translated transcription of the first part of the conversation.

Part 3 – La Cultura del Progetto: Andrea Branzi on Designing Culture

The series concludes with a conversation about broader cultural understandings of design, taking in the full scope of Branzi’s expansive work – including his roles as curator, writer, editor, and educator.

CR: Let’s get started.

AB: Excellent.

CR: Welcome back again, Andrea, for our third and final conversation. In fact I’m sad that this is our last session together because I’ve really valued our time…

AB: Me too!

CR: This morning, while I was preparing for today, I had fun listening to Schönberg, who I had not heard in some time. So thank you for mentioning him yesterday. Today’s conversation will begin with the idea of design culture. And I’m using that term in two ways today. The first is as a specific term, perhaps a specific term for your work. And the second way I’m going to use this word, this term, is as a means to explore the discipline or the broader career that you have pursued. So I’m referring to your work as a writer, as a curator of exhibitions, and as an educator.

Okay, the first question… Let’s start with a question of definition. In English, the Italian term cultura del progetto is translated as “design culture.” As a term, it essentially refers to the social, cultural, and perhaps even political and economic context, in which design exists. As a term it works because it means… Yes, it means that design does not exist in a vacuum. There’s always a context. But I believe that this phrase lacks the complexity of the Italian term. And so I’d like to ask you to explain what “design culture” means, in the sense of cultura del progetto.

AB: I have to admit that I’ve never known. I’ve never understood the term.

CR: Okay, we’re off to a good start.

AB: Because in reality my mode of working, and that shared as well by others whom I’ve known in the environment in which I gathered my experience, was never of the truly professional kind. I’d say it’s more like a domestic scenario, a very full house bursting with interfamilial connections, including both people and animals. That is, my work is not separate from my private life. Rather, the two are closely integrated. For example, in our story, or in my story… I’m married to Nicoletta, who is the sister of the other member of Archizoom. And then we’re related by marriage to another couple, Dario and Lucia Bartolini. And then… there’s a whole group of interconnected people. This is standard in Jewish culture, I believe, this practice of living a shared experience that is very creative and also very playful. All the projects that we did, at least the most important ones, were always… accompanied by a great deal of laughter. We shared immense joy in living and learning.

So it’s very difficult to distinguish professional activity from the context of everyday existence, of the rest of life, of experience, of culture. But I think that this is the case with many other people. Many people put together a group, or a troop, that is very rich in its intellectual and creative relationships. One’s profession is never precisely definable in the English manner. There is no precise linguistic definition. Because… Perhaps I never had a professional life as such. Maybe I never worked as an architect. Sure, there are encounters, questions, solutions, and proposals, related to certain requests, certain needs, that have been directed to me. But in general the relationship gets inverted. It’s a kind of activity that becomes almost independent at least in the best cases, when there’s a dimension of greater exploratory potential that is never perfectly circumscribed by a functional relationship. It’s always been a type of lifestyle… of being part of an exaggerated generation, where we’ve experienced great joy and had lots of fun as designers. So it’s not precisely… It’s not easy to define.

CR: So it sounds like it’s difficult to define it in Italian too. In part because it’s a great luxury to be part of an exaggerated generation, to have the opportunity to experience this kind of continual joy. That’s really wonderful. It sounds to me like it’s not just a Jewish thing, or a Jewish characteristic, let’s say, but also an Italian thing. What I mean is that the family business is a standard part of the Italian economy. I’m thinking of Pirelli, Fiat, Alessi. All of these businesses, at least at the beginning, were family enterprises. But also… But also the idea that there’s no separation between all the activities that you do and that you’ve done. Perhaps it’s not so surprising, when one thinks of the context in which you began. Because when I think of Ponti and when I think of older people like Ernesto Rogers, and all those people, they also had this idea or this multifaceted approach. Sure, they designed buildings and objects, but they also did exhibitions, and they wrote. So for you, is it something you always thought of doing as an architect? Did you always think you’d engage in all these different activities, like writing and doing exhibitions?

AB: Yes, even though my friends in Milan, who we’ve talked about a bit, those individuals who were so important and so professional… They were also great professional architects. They were extremely meticulous, very precise, very attentive to the needs of professional relationships. But we developed them in a different way, in part because our path, our cultural path, was never entirely or exclusively defined by the search for solutions, but perhaps by the invention of solutions to problems that we thought up ourselves, before a problem was posed to me that needed to be resolved. I’ll show you a picture of No-Stop City…

I see it!

…which we talked about yesterday. Oh, you see it? It’s pretty big. But…

CR: Indeed, it’s big. Thank you, Nicoletta.

AB: See it?

CR: Nice. Thanks for showing us.

AB: It was a design done… It’s preserved at MoMA in New York and represents, in contrast to an architectural design… Thank you. It represents something else. It’s almost like an abstract design. It doesn’t correspond to a precise geometry, but to a flow of various dynamic energies. And this is also a symptom of a mode of working that is not easy to define, even though it does have its own rationality. And then the playfulness that has always run through our work… But playfulness is a part… It represents a part of rationality. It’s never a simple game of cards. Rationality also comes from the affirmation of the comedy of life, of work, of art, and so it has aspects that are very different from a precise linguistic definition.

CR: But it’s still professional, only just a different mode than in London, or in Great Britain perhaps.

AB: Also because what we call a profession is a more complex activity. It’s a tableau of problems, of relationships, of functions, of solutions, but then there’s also an unpredictable component. I’m talking about the improvisation of design itself. So, for example, No-Stop City or also Agronica, are not proposed as solutions. Rather they’re avenues of approach to diverse problems. They’re different interpretations of the events of the history of time, the history of production. So it’s all much more interconnected, much more similar to an unpredictable narrative that may enrich the potential of design.

CR: Yes, it definitely enriches it. It’s interesting, because this idea that design asks questions in addition to, or instead of, having the answers, is something we think today. I teach at a design school and it’s normal for designers today, but it’s interesting to also think of it as an approach from 40 or 50 years ago, to think that it was already part of your work at that time.

Okay, I’d like to talk about or start with one of these activities, one of these grand energies, one of these grand confluences. And that’s writing. I’d like to know what the impulse is behind your great interest in writing, for example books like “The Hot House,” or “Learning from Milan,” which in Italian was called “Pomeriggi alla media industria,” but also shorter writings like your column for “Casabella” in the 1970s. What is it that attracts you to the printed word? Does it offer something different than designing objects, for example?

AB: In general, at least as it pertains to me, it’s a way to reflect about myself, as well as to create questions to think about. They’re never… In general, it’s not like I get a question to which I write a reply. More often than not, I’m the one who proposes the questions for myself to answer. I come up with them. In a certain sense I play a game with myself. So… the story never flows from an ordered thought process. There’s a core idea that stimulates me, a set of problems that stimulate me, but I only find the answer in the process of writing. I have to write about the problem directly. When I start… When I start writing, I don’t usually know exactly what path I should or could take. I make it up in the process of thinking. While thinking, it occurs to me that I could say this or write that. But I believe this mode of writing is rather common, rather widespread. Sometimes the path is clear, other times it’s more obscure, less obvious. But in any case, the path is always unpredictable. While I’m writing, I never know how it’s going to end.

CR: Your confession makes a lot sense because writing is a mode of thinking. Otherwise there’d be no… It’s also important for me. And it saddens me a bit, if that’s the right word in Italian, that there are so many designers, at least here, who think that design and writing are two different, even incompatible things. But actually, I hope that’s not the case. I hope they’re two different approaches that help us, or that help others, to think and communicate. So, do you write every day, or only with a book or a project in mind, or when you have a question to ask?

AB: In general, there’s always an occasion that I’m writing for. Or there’s a magazine that asks me to write something. Or I get asked a question, like the one you’re asking me now. And then I have to extemporize. I don’t know exactly what the right answers might be. Or the right answer. I’m always interested… Questions always interest me. Because I don’t know what the answer is, and so… And so it’s a mode of working that is very peculiar, but I think also very common. Ultimately, I’d never be able to tell a story like in a novella. I could never imagine how it would begin and end. I might be able to find a way to start it, but then I’d have to make up the end. I wouldn’t know ahead of time what the ending would be like.

CR: I like your honesty on this point. But is the ending sometimes an object? Is that the relationship between writing and objects for you?

AB: Yes, in fact I try to start designing an object and while… At the start, I don’t know exactly what it will end up being. I might start from one point but then head towards another. And then in the end, I find something that stimulates me or… something that seems strange, and the design develops. The design develops like that. In a certain sense, it develops in the dark. I remember how No-Stop City began. I remember the very moment when that manner of designing was born, that manner of thinking. But beforehand, at the beginning, I had no intention of doing it. But then, once I started designing it, the idea suddenly slipped out and entered this other dimension that… in which… in which I didn’t even know where I was going. But then, after a bit, I said, “Hey, this is interesting. It’s interesting that this thought is something I’ve never considered before.” And I remember that I called Massimo Morozzi over. I showed him the design and asked him, “What do you think of it?” And he, who was more intelligent than I was… Much, much more culturally refined. We looked at it for a while and then he said, “This could be very interesting.” Then after a while he said, “Now I understand what you’ve been drawing.”

We also talked about it with the others, with Paolo and Gilberto, and they also said, “These ideas should be developed further, formulated more clearly. Yes, it’s a transition away from the traditional design process toward a more fluid one,” and so on. It was then developed in No-Stop City and then in the whole mode of working of the following years. And it continues today, in work that appears to be totally unrelated to No-Stop City and with this idea of flow. You’ve seen that design that I had Nicoletta show you. It’s no longer an architectural design. Because… Nicoletta and I saw it again at MoMA, where there was a smaller-size room devoted to architecture. There were some small architectural models by people like Aldo Rossi, Mangiarotti, and people like that. Gregotti. All of them were highly complex compositions, clearly very laborious, irksome, you could say.

And then there was this design that… I’d forgotten all about. Because it had been done for the Gilman Paper Company, which was a big company that produced drawing paper and that had donated the design to MoMA. And when we… saw that design that you just saw now, we were absolutely surprised because it’s so clear, so empty, showing no trace of the laborious effort of creation. Instead it has a rationality of its own, its own kind of rendering of an unlimited metropolis, and so on. And so it was a great consolation to see this drawing that we’d forgotten all about. Forgotten in the sense of a single object. It wasn’t easy… to identify anymore. I’m laughing while reflecting on this design.

CR: That’s truly a beautiful memory. But it makes sense, because this drawing has… has a status, has a role that’s totally different, a vision of the world that’s totally different from the others.

AB: Completely different.

CR: Indeed.

AB: This tendency to laugh, which might seem somewhat of a provocation, actually corresponds closely to my mode of working, I believe. There are other friends of mine and important intellectuals, who have a dramatic tendency that’s very powerful, very historic, very closely linked to an intellectual tradition, whereas for me it was always… And this is also a limit of my approach to working. For me it was always an opportunity for happiness, for joy, for fun, for… And it can seem a bit provocative. But it’s a way… It’s part of my rationality. I’m not irrational. I couldn’t call myself irrational. I’m a rationalist for whom being playful is part of my rational dimension, of laughter, of having fun. It’s a mode of intellectual play.

CR: Precisely so. Having fun or laughter or joy is not the same as not being intellectual or culturally refined. Indeed, it’s part of it. It’s an exquisite way of being.

AB: Yes, that’s true.

CR: Yes.

AB: Okay. Okay, let’s think… You talked about an exhibition. So, I’m going to use that recollection to now talk about exhibitions. We’re going to move away a bit from writing. No, I actually have another question about writing. Is there anything you’re working on right now? Is there a new book or a new article or a new problem that you would like to work on, or are already working on?

Well… Seeing as how it’s always an apparent improvisation, both when it comes to design and when it comes to work, including in the organization of exhibitions and so on, it’s rather difficult for it to be clear to me from the beginning what I might do. I always need some sort of stimulus, or some sort of improvisation, to get going. I need a thought or an intuition to get going, a possible solution to a problem that I can never articulate clearly. And when I write, for a magazine for example… Or I’ve also ended up writing various books that you could also say are devoted to history. For example, “Introduzione al design italiano,” and so on. Even in those cases, I began writing without having a clear idea of what I wanted to say exactly. But then in the course of writing, everything becomes clearer, I start to get interested, I start playing mentally with… Even if the topics are very serious and there’s nothing to laugh about. Still, the absence of laughter is part of… It’s also a game, it’s something that’s unknown to the mind. So, it’s difficult to explain my work methods. I wouldn’t even really know what they are.

CR: But you said it’s important to have an external stimulus or a commission, or maybe even something you read in the paper. It’s like that for me too. You read something, and it might be 15 days later that something occurs to you to explore. Okay, then, now I’d like to talk about another large part of your work, namely what we call “curating” in English, curating exhibitions. And this is also a peculiar aspect of Italian history, I believe, because you have curated many, many exhibitions. But this was a key activity for numerous Italian architects. And historically, this seems perhaps to correspond a bit to a lack of commissions for built structures. Perhaps not for you, but for other architects. But also to the opportunities afforded by the strength of the exhibition world in Italy. I’m thinking of the Triennale, for example, but also of the patronage of galleries and of industrialists. In comparison with other design cultures or culture del progetto, there’s a particular context for exhibitions and architects in Italy. That having been said, I’d like to ask you now what it is about exhibitions and curating them that interests you.

AB: Yes, well… naturally there are very different kinds. There are exhibitions that I do with my own work, where I show my own work in an exhibition, and that’s pretty widespread. But then there’s another kind of exhibition, where the show is devoted to other topics or other people. But in a certain way, these two different models become one single model. Because… even an exhibition devoted to other people such as for Ettore Sottsass or other occasions at the Triennale… In the end I have to turn them into… into my own. The only way to organize an exhibition is to invent it. I don’t seem to have anything to do with it, but it’s the only way… Still, I think all the great curators, who are much more professional than me and so on… In the end, they always exhibit themselves, even if the works shown are by other people. There’s always a move in the direction of self-representation, of self-portraiture.

The self-portrait is characteristic of… Objects are used that aren’t mine. Stories are told that are not related to my own experience. But in the end, an exhibition emerges where I have given… Where you could even say I’ve given a gift to someone. I’ve given them an image of their work that didn’t exist before, a different interpretive key, and this attracts me and is a lot of fun for me. It’s a game where I don’t know the solution, but in the end, an exhibition results that is of my making but that does not include my professional work. Rather it’s an intellectual and creative contribution that I myself discover. When I start working on the exhibition, I discover solutions that I had not foreseen.

CR: I like this almost psychological interpretation of the curator as engaging in self-portraiture, as you said. It’s interesting, in part because I… And I’m not some great curator, but I have curated a few exhibitions. And I like it a lot. It’s a very creative, yes, a very creative process. In fact, I saw… In 2016, I saw the exhibition “Neo Preistoria,” or “Neo-Prehistory,” at the Triennale. That was one of your exhibitions, obviously. Thinking of what you’ve said and also thinking about your history, did you see that topic as an opportunity to revisit the concept of neoprimitivism? Sorry, I can’t get the words out right today. Or was it something that provided a stimulus for that exhibition?

AB: Well, that exhibition was a collaboration with Kenya Hara from Japan, a very important person, and together we began to consider the idea of doing a big exhibition at the Triennale. And then, when we started planning it, conceiving it, it wasn’t at all clear at the outset what we were going to do. But then, when we were getting it ready, setting it up, then the words, the names, and then a framework emerged that… Yes, and then it became perfectly clear that the idea of neoprimitivism should be the theme of a big exhibition, in part because this friend was an extremely intelligent person. His contribution to this exhibition was genius. Then I wrote the introduction, the explanation of what I was thinking about. But at the end of the exhibition, when the exhibition was over, it became clear where the exhibition ultimately came from, what it was all about, namely the idea of a modern world that is very… of a contemporary existence that is very similar to the condition of primitive humans, who did not have a past or a future but simply a continuous present.

And we’ve talked about that, the idea of living in a neoprimitive world devoid of future prospects, devoid of… full of discoveries that are made suddenly and every day, but not foreseen, not intended. That’s how I think things were in the era of primitive human beings, in which every day a discovery was made, but it was never the result of a pre-established plan having been fulfilled. It was an accident, a surprise, a miracle. This is also a bit how we can understand the culture of design, which always needs to come up with something different. We talked about this. In design there are never… two buildings or structures that are exactly the same. Everything in the world is different, the product of chance, just like in painting, like in art, like in music. Constantly new. Constantly different. That’s why it’s necessary to have a certain agility. And lightness. Because if… if the work gets weighed down, if it gets heavy, you lose your momentum. It all becomes uselessly laborious. You have to play around with surprises, be receptive to surprises. And they can be very serious. Indeed, in general they’re all very serious. They’re not useless games. There is also an aspect of uselessness, but that’s part of science, of innovation, of creation. It’s not part of a game that is foolishly stupid or infantile. Doing this… also matures you. Because in reality, this activity is not easy or simple. It’s a complicated activity.

CR: In fact, you said… You used the word “agility.” And this seems to me to be a very important ability for architects and designers to have, because the world is changing every day. And so the architect has to respond and stay ahead of these changes in order to think. And so, thinking specifically about that exhibition at the Triennale, and thinking about the question I asked earlier about writing, is there also a relationship between the activity of curating and designing? Thinking of 2016, the year that exhibition was held, it was the same year you created the “Planks” series for the Friedman Benda Gallery. That project has an echo, you could say, of neoprimitivism. Were those two projects somehow parallel or did they inform each other, or is it simply a coincidence?

AB: Could you please repeat the observation, the question for me?

CR: I’m sorry, it seems to me that in the same year… And maybe I’m making a connection here that’s too simple or direct. But it’s striking that in the same year you curated the exhibition devoted to neo-prehistory, you then returned to that topic in the objects in the “Planks” series. And I’m curious to know if there was a connection.

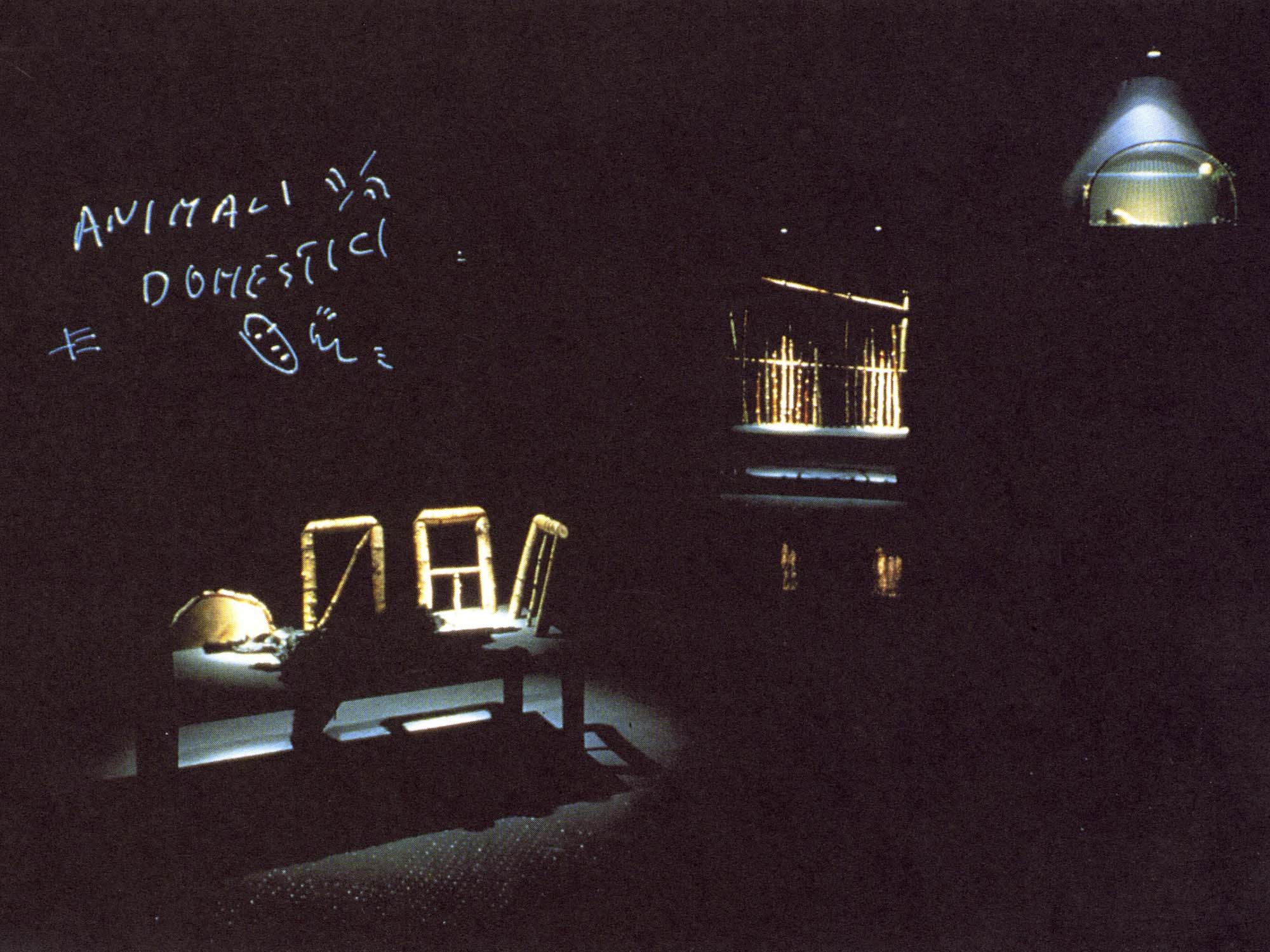

AB: Yes, I believe they are closely connected because they came… In fact, “Animali Domestici”… “Animali Domestici” features tree trunks, i.e., it incorporates elements as they exist in nature. It’s never… a rational correspondence. It’s always a primitive exploration. So in a certain sense they’re closely connected. And the designs I’m working on now are very similar.

CR: Ah, this seems like a… a precious glimpse into your work, thank you.

AB: But I’m doing these designs here for Marc Benda. They’re taking shape at the same time as I’m working on something totally different: a continuous series of images of a marionette. Of a Pinocchio. With a long nose. And I’ve done almost 100 of these drawings. This is also a kind of “no-stop” thing in a certain sense. It’s something… I don’t really understand where it comes from or where it’s going. But maybe the only way to work is not to know precisely where you’re going. In writing as well, it’s important not to know precisely what the final message is going to be. It emerges in the process of writing.

CR: In fact, that’s also how our conversations are. We have a framework, but we don’t know exactly where we’re going. It’s nicer that way. In fact, another… The third element, let’s say, of your ample work that I’d like to ask you about today, is education. I see it as another context, another manifestation of your practice. You were not only a student, obviously, but also an educator, and also someone who created the terrain for others to learn in, with Domus Academy but also in your role as chair of Interior Design at the Politecnico di Milano, a position you held until 2009. And at this point I should say that I was a student in Milan in the early 2000s and that I took one of your courses, and that it made a big impression on me. At that point, I never dreamed I’d be talking to you like I am today. But we’re not talking about me. I’d like to know what interests you about education, about creating these atmospheres, or this particular space of a design school, where diverse ideas and generations meet.

AB: Well, let’s say that… For example, No-Stop… Teaching at the school of the… Domus Academy… Domus Academy was very different from teaching at the Polytechnic because… at Domus Academy there was a continuous discovery of topics and individuals, of teachers and classes, students who came from all over the world. And so there was a great continual discovery there. It wasn’t clear to anyone what we were supposed to be getting at. But the case at the Politecnico was similar but somewhat different. Because the university is a very complex organism, full of diverse functions, expertise, and specializations, where each instructor has their own individual logic and so on. In contrast, at Domus Academy there was a continuously evolving community. But as far as I’m concerned I always tried to… More than being a professor who teaches, I tried instead to be someone who learns. I tried to create autodidacts, people who learn to design on their own. And they do that by teaching me how to design.

I tried to help the students be explorers of themselves. All students are gifted. They’re all capable. The job of a teacher is to be a midwife, to bring out this creative ability, not to make them reflect on my creativity. In fact, if there’s anything that bothers me, it’s those students who try in some way to imitate my mode of working. That’s not useful at all. It’s an endless mirror. That’s worthless, whereas helping them to be autodidacts means creating a mental structure that is much more realistic, because the world that students will find when they leave the university is very complex, very unpredictable, very… It doesn’t teach you anything. You have to have a certain maturity, a certain autonomy. You have to be the kind of person who can walk around on their own legs, not on mine. That would be worthless. I have to help them mature. So it’s an approach that’s rather… upside-down, the approach that says the university should help students become autodidacts. In general, when professors hear proposals of that kind they’re shocked.

CR: Of course they are.

AB: They think it’s a mistaken method. But then in the end, they realize that it’s the only way to help students mature, help them grow, become self-confident, invent something new. It requires pushing them every time with questions and not proposing solutions to them. These are methods… that I’ve learned a lot from. They’re procedures that I’ve learned a lot from, because I didn’t have anything to teach but much to learn.

CR: That’s a big…

AB: That’s how I’ve always been. As a student, I was always a disaster. A disaster.

CR: A disaster?

AB: But then at the university, I was excellent. I was a much better student, but… because I was the one who decided what I studied and what I learned, whereas in school and high school we were always questioned without warning and we had to do work that was assigned to us. It was all one big terrible game, full of danger, mistakes, fear, and so on, and so it didn’t work. But the university worked perfectly, because I was the one who learned. It wasn’t the professors who taught me.

CR: It seems to me that this mentality of the teacher or the university professor, and also of the student, is very important for understanding the peculiar nature of the relationship between teacher and student. Also, as you said, the importance of autonomy. And curiosity, that’s a big thing. But that requires a great deal of humility on the part of the professor. And I imagine that all those professors who are shocked… That’s part of the problem.

AB: Yes.

CR: Being an expert also means that people aren’t always humble, but you do have that quality. Okay, we’ve almost come to the end, I believe. I have too many things to ask. But there is a person I’d like to talk about before we finish, and this is also a way of returning to a topic from our first conversation, namely the subject of modes of working. And in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, working as part of a group was very important for you. Like in Alchimia and Archizoom.

AB: Yes.

CR: But it seems to me that after that period, let’s say, you became more of a soloist in a certain sense. Except perhaps for the role played by Nicoletta in your work. And so I have to think of… Besides projects like “Animali Domestici” and the “Coppia Metropolitana” that beautiful tapestry you did together so many years ago… But also when I was watching the video of the installation at the Fondation Cartier, you see Nicoletta working on the installation. And I wanted to ask: What is the nature of the collaboration the two of you have?

AB: Well… Our collaboration grew out of the mode of working that already existed in Radical architecture, in the Archizoom group. Because she was the sister of Massimo Morozzi, and their sister was Dario Bartolini’s wife… Lucia Morozzi… Lucia Morozzi. So there was this whole smorgasbord, a smorgasbord of relationships in which we share our work with each other, we stimulate each other, both in the games we play and in the development of ideas, in the questions we ask and the solutions we propose. It’s not… There aren’t any… There’s never been a definitive hierarchy, but rather a game that pursues an important intellectual growth that is in part based on massive differences in cultural sophistication. Nicoletta is much more culturally refined than I am. She has an incredible memory, whereas I always forget things. My memory has always been bad and it keeps getting worse. But this… I don’t speak English. I never learned it. I don’t know it. She knows English, French, Japanese. She can read and speak them. That’s rather rare. She reads all the strangest books. She has a vast range of knowledge. She’s very serious about literature, history, and so on. Whereas I never… In my life I… This isn’t a paradox. I’ve never read a book about architecture or design.

CR: Really?

AB: Only when I studied architecture, to prepare for certain exams. But I was never interested in them, because either they talked about things that I already knew and so they were of no use, or they were about things I didn’t know about and so they didn’t stimulate me. They even got on my nerves a bit. Reading a few books, on the other hand, is like reading all of them. It’s not that important. It’s a method that’s a bit unorthodox. With books, you either read them all or you don’t read any of them. That doesn’t mean you should be ignorant.

CR: No, no.

AB: It means having a different creative process, a different whatever it is in my creative process and in hers. However, this is what happens.

CR: So they’re two modes, They’re two types of knowing or…

AB: Yes.

CR: They’re compatible. Only I see all those books behind you.

Nicoletta: They’re mine.

AB: They’re Nicoletta’s books.

CR: And these are all my books on the history of design. Actually, I never read them because I don’t have time. Now we really are…

AB: But our relationship is also based on love. So it’s not just a professional working relationship.

CR: Of course.

AB: So it’s all more… It’s not all that clear.

CR: But it’s a very beautiful thing to have someone with whom you can think every day… think about the world. So now I have one last question, seeing as how we’ve come to the end. And this question is more about the future. What do you still want to do? For a moment you showed us a project that you’re working on right now. But are there ideas you’d like to explore or challenges faced by our troubled world that interest you? Or what is the next chapter for you?

AB: Well, I understand the question but I don’t have an answer, because so much is based on improvisation. So, for example, when I said that I’ve done 100 drawings of a marionette, I started without any clear idea. I didn’t have a clear idea. I didn’t know why I was doing it. I didn’t know what the use was in doing 100 drawings of a marionette. But once I’d done them, I understood that they were part of a story without an end that could go on to infinity. And… For example, a very complicated book has just come out that is called “The Project…” This book.

CR: Ah, yes.

AB: It’s also in English.

CR: Okay, I have to read it. I hadn’t seen it yet. Great.

AB: “The Project in the Age of Relativity.” It contains 600 pages of my theoretical writings. It was edited by Elisa Cattaneo, a professor at the Polytechnic University of Milan. It took six years to collect all these theoretical texts. And… But… to be completely honest, and I’ve said this many times, this book is the work of Elisa Cattaneo. I didn’t… It’s her book. Over time, over many years, I elaborated these theoretical ideas. I modified them every time, but in the end, it’s a large mass of thought that… They’re starting to think of doing a second volume.

CR: Really? Another six years and 600 pages of text.

AB: It’s a heroic undertaking and I didn’t help at all because… The idea of reading my own texts is the last thing that might interest me. Every now and again I scan it and see a piece, but I already know it all. It’s all obvious to me. But there’s a lot of interest in this kind of gigantic collection. 600 pages with an introduction written by Charles Waldheim, who is a dean at Harvard University. So it’s a very important book. It also includes many contributions by other theorists and historians who were very… very keen to work on this… on this type of collection, this type of story. It’s also a bit… It’s also a kind of “no-stop” thing. It goes on and on. It could continue in a second volume and also in a third. For example, for many years now, I’ve been writing a steady column for the magazine “Interni.” They ask me to write a short piece every month. A short introduction to a design or an image. And I’ve been doing this for many, many years. I don’t know how long, but really for very many years. And then there’s always the threat that they’ll collect all these introductions…

CR: The threat!

AB: Put them in another “no-stop” volume. But that can’t happen because the job would be too… From the point of view of editing, it would be a gigantic undertaking. It would take ten volumes, so…

CR: Someone needs to get started right now. That’s what you’re saying. But that makes sense to me. Naturally there’s a great deal of interest in your work. That’s obvious, but there’s also a desire to create an archive of your work. It’s great that there are people who are doing it for us. We always want to know more.

AB: There’s a… Nicoletta is also involved in this attempt to construct an archive. And then in Parma there’s the historical archive of my work. It’s an enormous quantity of work, of thought, of designs, of models, of drawings… All this… is happening… It’s a way to… It’s probably also a way to forget, to go beyond memory, the failure of memory. Laziness, the failure of memory, produces these kinds of defects and problems. Do you understand?

CR: In what sense?

AB: For example, in the sense that the archive in Parma is an oversized horde of ideas, designs, messages, and so on, that in a certain sense is also a means of removing this memory.

CR: Because it’s put in a tiny box? Well, in a large building. But it contains your history like that.

Nicoletta: It’s for you.

AB: What?

Nicoletta: It’s a way for you to…

AB: Yes.

Nicoletta: Not for others.

AB: Right. It’s a way for me. But this has always happened when it comes to people’s work. Either you have a great memory, or you don’t. No one mode is better than another. It’s not like they’re indispensable. There may also be other solutions. This is one of them. But there are also people who have a great memory. They manage to organize an archive. Nicoletta and others are like that. What?

Nicoletta: Lorenza. Lorenza.

AB: Oh, Lorenza. My daughter Lorenza. Such people really get into this kind of work devoted to…

CR: …to history.

AB: …to memory. To reconstructing events.

CR: Well, we’re very grateful for all this massive work that your daughter, your wife, these museums, CSAC, and everyone is doing. And in fact, in these three hours that we’ve had together, we haven’t even talked about ten projects, even though you’ve done 100 such projects. But unfortunately at this point we have to finish our conversation together. I can’t tell you how grateful I am for our time together.

AB: I learned so much.

CR: I’m grateful.

AB: And at this point you should agree to stop being so formal with me. But apart from that, this conversation was an opportunity for me to learn a great deal. It’s been very intelligent. Your questions and your ideas, your stimulating responses. A conversation needs two interlocutors. If not it becomes… Every now and again… Very often I get questions that are utterly banal and it becomes very laborious to respond, and then that’s the end of it. On the other hand, if the conversation partner is intelligent, attentive, sensitive, then everything is much easier. Obviously, everything is much easier.

CR: I also have to thank you for that, my friend. So there, I’ve finished with a less formal tone.

AB: Thank you. Good luck with your work.

CR: You too. Okay, thank you very much. And goodbye. Have a good day.